www.space.com

NASA Mars lander makes 1st ever map of Red Planet underground by listening to winds

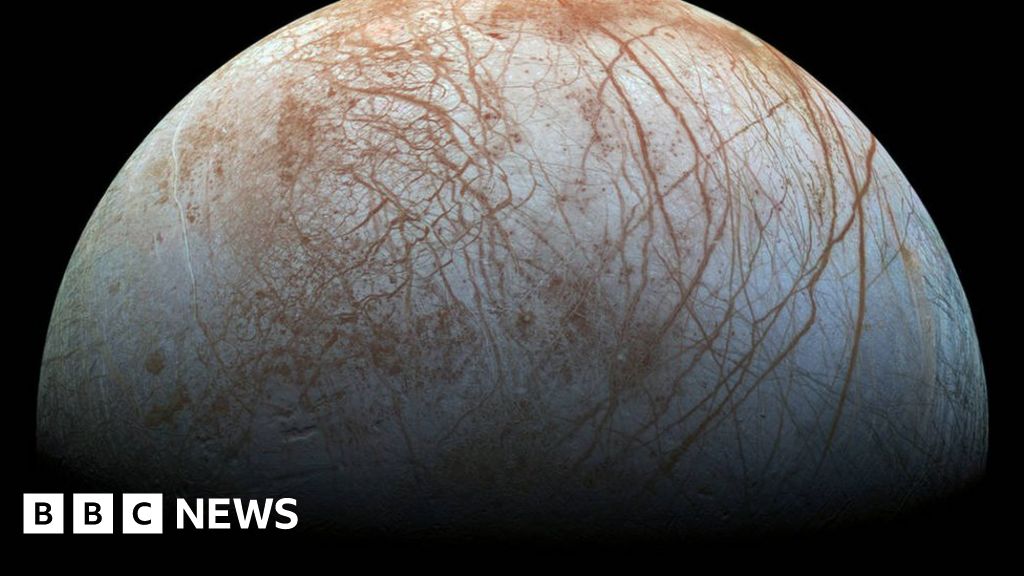

Researchers have created the first-ever map of the Martian underground by listening to the sound of wind reverberating through the layers of soil and rock near Mars' equator.

Science & Tech

Researchers have created the first-ever map of the Martian underground by listening to the sound of wind reverberating through the layers of soil and rock near Mars' equator.

The team used instruments on board NASA's InSight probe, which landed in the flat Elysium Planitia in 2018 to study weak "marsquakes" rippling through the planet. InSight's data has previously enabled scientists to get a rough idea of the size and composition of Mars' core, as well as the nature of its mantle and thickness of its crust.

A new technique developed and finetuned on Earth now for the first time enabled a team led by Swiss geophysicists to use the lander's instruments to peek directly underneath the planet's parched surface and discover what lies within the first 660 feet (200 meters) of its crust.

"We used a technique that was developed here on Earth to characterize places for earthquake risk and to study the subsurface structure," Cedric Schmelzbach, a geophysicist at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich (ETH), and corresponding author of the new paper told Space.com.

"The technique is based on ambient vibration," Schmelzbach said. "On Earth, you have the oceans, the winds, that make the ground shake all the time, and the shaking that you measure at a certain point has an imprint of the subsurface."

Essentially, the commotion on the surface makes the ground vibrate. These minuscule vibrations propagate deep into the subsurface and can be picked up by sensitive instruments.

Mars, Schmelzbach said, is much quieter than Earth. There is no ocean on the planet and Mars' atmosphere is much thinner, resulting in a weaker, more feeble wind. On top of that, while on Earth geologists could use countless stations, on Mars, they only have one — the InSight lander.

Yet, listening to the interaction of the Red Planet's winds with the ground underneath its craters and plains revealed the subsurface structure in astonishing detail.

"The resolution gets coarser the deeper we get," said Schmelzbach. "Close to the surface we can resolve layers that are one meter [three feet] thick. But in greater depths it is really a few tens of meters [10 meters = 33 feet]."

The map provides a fascinating glimpse into the past several billion years of Martian evolution. It reveals an unexpected layer of deep sediments as well as thick deposits of solidified lava, all covered with a 10-foot-thick (3 m) blanket of sandy regolith.

The surprising sedimentary layer, the origin of which is still a mystery, is located 100 to 230 feet (30 to 70 m) below the Martian surface, sandwiched between two solidified layers of ancient lava.

"We're still working on how to interpret that and how to date how old this layer is," he said. "But it tells us that probably the geological history at that site is really more complicated than we originally thought and that probably more processes had happened in the past at that place."

The researchers compared the two lava layers embracing this sediment with previous studies of geology of nearby craters. This data enabled them to place the origins of those layers into two important periods in Mars' geological history some 1.7 billion and 3.6 billion years ago.

On top of the younger lava layer, just below the surface regolith, is an approximately 50-feet-thick (15 m) band of rocky material likely stirred up from the Martian surface by a past meteorite impact that then rained back down to the planet's surface.

In the future, the scientists would like to see whether they could stretch their technique a little further and look even deeper, within the first few miles of Mars' crust.

"We have kind of a blind zone there at the moment," said Schmelzbach.