www.space.com

Who was James Clerk Maxwell? The greatest physicist you've probably never heard of.

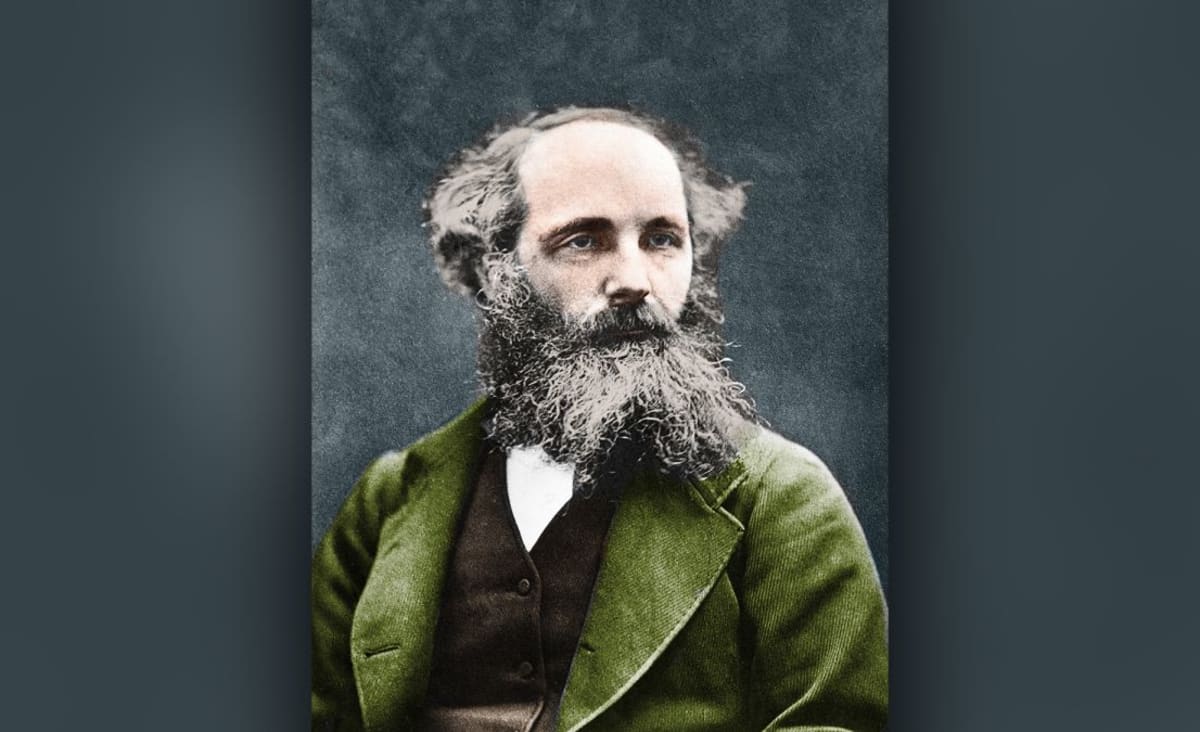

James Clerk Maxwell is the scientist responsible for explaining the forces behind the radio in your car, the magnets on your fridge, the heat of a warm summer day and the charge on a battery.

Culture & Entertainment

Paul M. Sutter is an astrophysicist at SUNY Stony Brook and the Flatiron Institute, host of "Ask a Spaceman" and "Space Radio," and author of "How to Die in Space."

Everyone's a fan of Albert Einstein, and for good reason: He invented at least four new fields of physics, spun a brand-new theory of gravity out of the fabric of his own imagination, and taught us the true nature of time and space. But who was Einstein a fan of?

James Clerk Maxwell. Who? Oh, he's only the scientist responsible for explaining the forces behind the radio in your car, the magnets on your fridge, the heat of a warm summer day and the charge on a battery.

In the beginning

Most people aren't familiar with Maxwell, a 19th-century Scottish scientist and polymath. Yet he was perhaps the single greatest scientist of his generation and revolutionized physics in a way nobody was expecting. In fact, it took years for Maxwell's peers to realize just how awesome — and right — he was.

At the time, one of the great focuses of scientific interest was the strange and perplexing properties of electricity and magnetism. While the two forces had been known to humanity for millennia, the more scientists studied these forces, the weirder they seemed.

Ancient people knew that certain animals, like electric eels, could shock you if you touched them and that certain substances, like amber, could attract things if you rubbed them. They knew that lightning could start fires. They had found seemingly magical rocks, called lodestones, that could attract bits of metal. And they had mastered the use of the compass, albeit without understanding how it worked.

By the time Maxwell stepped in, a wide variety of experiments had expanded on the weirdness of these forces. Scientists like Benjamin Franklin had discovered that the electricity from lightning could be stored. Luigi Galvani found that zapping living organisms with electricity caused them to move.

Meanwhile, French scientists found that electricity moving down a wire could attract — or repel, depending on the direction of the flow — another wire and that electrified spheres could attract or repel with a strength proportional to the square of their separation.

Most bewilderingly, there seemed to be a strange link between electricity and magnetism. Electrified wires could deflect the motion of a compass. Starting the flow of electricity in one wire could spur the flow of electricity in another, even if the wires weren't connected. Waving a magnet around could generate electricity.

All of this was absolutely fascinating, but nobody had any idea what was going on.