This post may refer to COVID-19

To access official information about the coronavirus, access CDC - Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

www.nbcnews.com

Hong Kong's timeline since the 1997 British handover to China

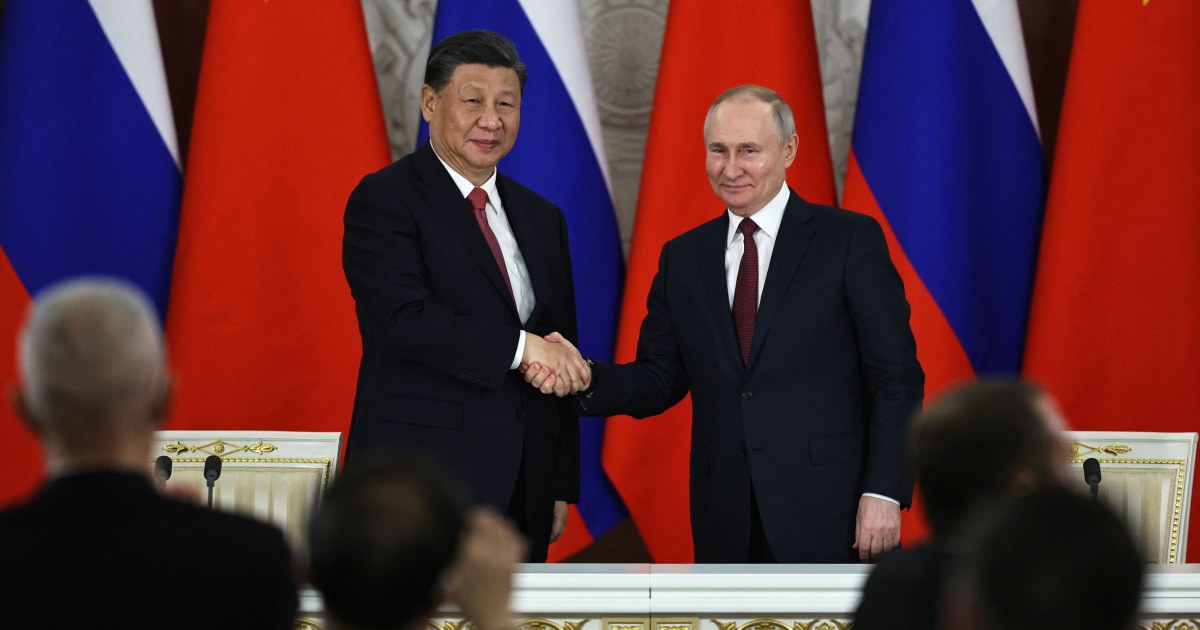

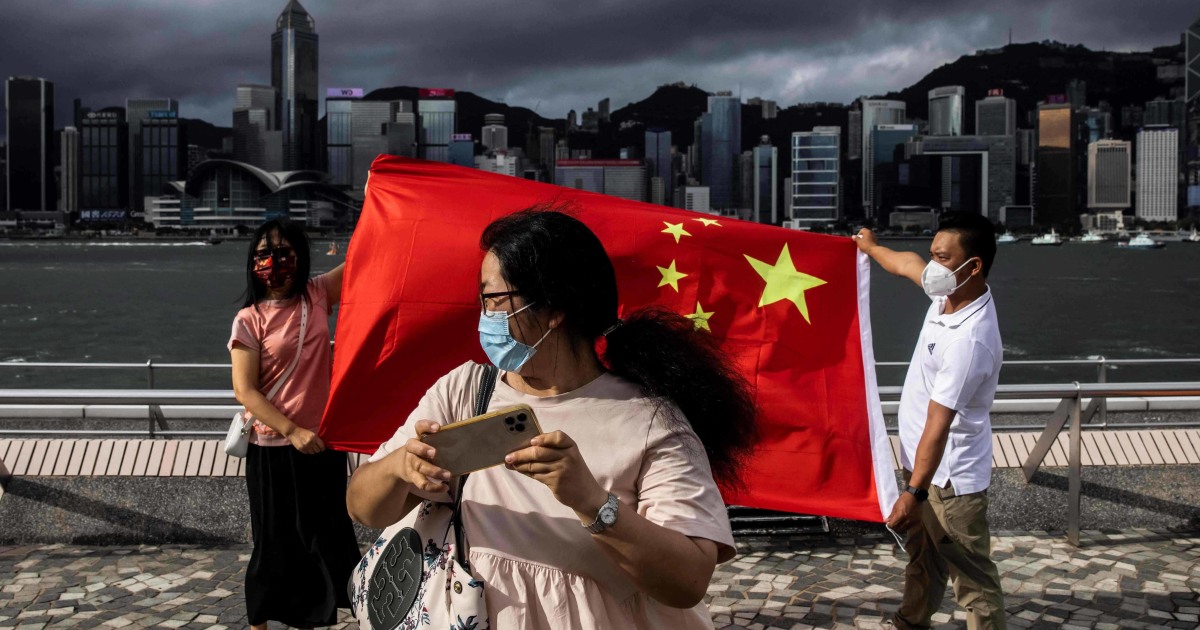

Chinese leader Xi Jinping made a rare visit to Hong Kong this week to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the city’s handover from British to Chinese rule. Here are some of the key political events that have shaped the city since then.

International

Chinese leader Xi Jinping made a rare visit to Hong Kong this week to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the city’s handover from British to Chinese rule and swear in its handpicked new leader, John Lee, who as security chief oversaw a harsh crackdown on dissent.

The 1997 handover agreement had promised Hong Kong would enjoy a high degree of autonomy and remain unchanged for 50 years, a promise that pro-democracy activists say has been broken as Beijing increasingly asserts its rule. Here are some of the key political events that have shaped the city in the last quarter century:

1997: The handover

Hong Kong had been a British colony since 1841, when it was occupied by British forces during the first Opium War. China’s Qing Dynasty signed it over to the British the following year in the Treaty of Nanjing, the first in a series of what China now calls the “unequal treaties.”

Under the terms of the Sino-British Joint Declaration signed in 1984, Hong Kong was to return to Chinese sovereignty as a special administrative region governed by a principle known as “one country, two systems.” The formula allowed the former colony to preserve its pre-handover freedoms that did not exist in mainland China, and to largely manage its own affairs.

The handover ceremony took place at midnight July 1, 1997, attended by Chinese, British and other international diplomats and representatives.

Hong Kong-born Bryan Ong, a 42-year-old antique collector in the city, remembers it vividly.

“I could tell there was a lot of emotion in the crowd,” he said. “I knew this was an extraordinary moment, a new chapter in the history of Hong Kong.”

2003: Article 23 protest

Six years after the handover, proposed national security legislation raised fears that it could threaten Hong Kongers' rights, such as free speech, freedom of the press and freedom of assembly. More than half a million of Hong Kong’s 7 million people marched against the bill on the July 1 anniversary of the handover, forcing the administration to shelve it. Subsequent attempts to revive the bill met widespread public opposition.

The proposed legislation sought to satisfy a requirement under Article 23 of the Basic Law, Hong Kong’s mini-constitution, that the city enforce its own laws criminalizing treason, sedition and secession against the central government in Beijing.

2012: Moral and national education controversy

In mid-2012, the Hong Kong Education Bureau proposed a new mandatory subject for the city’s public schools: moral and national education.

The curriculum, which included teaching materials extolling the achievements of the Chinese Community Party and criticizing multiparty systems like that of the United States, set off a series of mass protests. Critics said the move was an attempt by the Beijing government to brainwash the city’s young people with pro-mainland propaganda.

Tens of thousands of teachers, students and parents demonstrated at government headquarters for 10 days. In response, the government withdrew its proposal and allowed schools to choose whether to teach the subject.

2014: The Umbrella Revolution/Occupy Central

A 2014 decision by the central Chinese government to preselect candidates for Hong Kong’s top job dashed hopes that the city would achieve the promised goal of genuine universal suffrage.

The move coincided with a civic disobedience movement coordinated by three pro-democracy advocates, including law professor Benny Tai. The Occupy Central with Love and Peace movement aimed to paralyze the city’s main financial district to force the government to allow fully free elections.

Police efforts to clear the roads with tear gas prompted early protesters to shield themselves with umbrellas, giving the movement its other name: Umbrella Revolution.

The sit-in, which began in September and brought activists like Joshua Wong to international attention, spread outward from the city’s government offices, eventually blocking key roads in three major districts and polarizing public opinion toward the movement.

The protest camps were cleared after 79 days, bringing the movement to an end without Beijing granting any of its demands for broader democracy. But a new generation of pro-democracy leaders had been inspired by the experience.

2016: Legislative disqualifications

Undeterred by the stalled 2014 movement, young pro-democracy advocates sought to change the system from within by running for seats in the city’s legislature. Though some candidates were barred from running over questions about their views on Hong Kong independence, others were elected.

At the beginning of the new legislative term, some activists used the oath-swearing ceremony to stage protests against the central government, with activist Sixtus “Baggio” Leung holding a flag that read “Hong Kong is not China” during his oath. The series of protests resulted in six elected representatives being disqualified from taking office.

2019: Anti-extradition protests

In early 2019, following the murder of a Hong Kong woman by her Hong Kong boyfriend while on holiday in Taiwan, authorities proposed an extradition bill allowing fugitive criminals to be sent for trial in places without extradition agreements with Hong Kong, including Taiwan and mainland China.

The bill exposed Hong Kongers to mainland China’s opaque legal system, raising fears it could be used to target pro-democracy elements in the city and further curb its freedoms. Protests against the bill swelled throughout the summer as reports of police brutality against demonstrations and authorities’ initial unwillingness to withdraw the bill fueled further protest demands.

The biggest protest, organizers said, drew as many as 2 million people.

Although the extradition bill was eventually withdrawn, protests persisted into January 2020, when Hong Kong confirmed its first case of the coronavirus. More than 10,200 people have been arrested over the sometimes-violent protests, which authorities sought to paint as a series of riots funded by foreign powers. About 2,850 have been prosecuted, with many imprisoned for years.

2020: National security law

In response to the 2019 protests, Beijing imposed a national security law on Hong Kong, saying it was necessary to restore order. The law, promulgated on the eve of the handover anniversary, made secession, subversion, terrorism and collusion with foreign powers punishable by life in prison. It also allowed for suspects to stand trial in mainland China. Foreign governments and rights activists have criticized the law as vaguely worded and draconian.

The law has since been used to target and shut down Hong Kong’s political opposition. Almost 200 people have been arrested under the law, including 81 opposition leaders, 92 ordinary citizens with no previous public profiles, and 15 journalists, according to the Hong Kong Democracy Council, a nongovernmental organization based in Washington.

The overwhelming majority of the city’s pro-democracy figures are now behind bars, have withdrawn from public life or are living in self-imposed exile.

Mass arrests and raids at the city’s pro-democracy newsrooms have spread fear across the city, leading independent media outlets and scores of unions and other civil society groups to shut down.

Lee, Hong Kong’s new chief executive, has said one of his top priorities is to enact the Article 23 legislation that failed in 2003, raising fears that the city’s freedoms will be further eroded