www.nbcnews.com

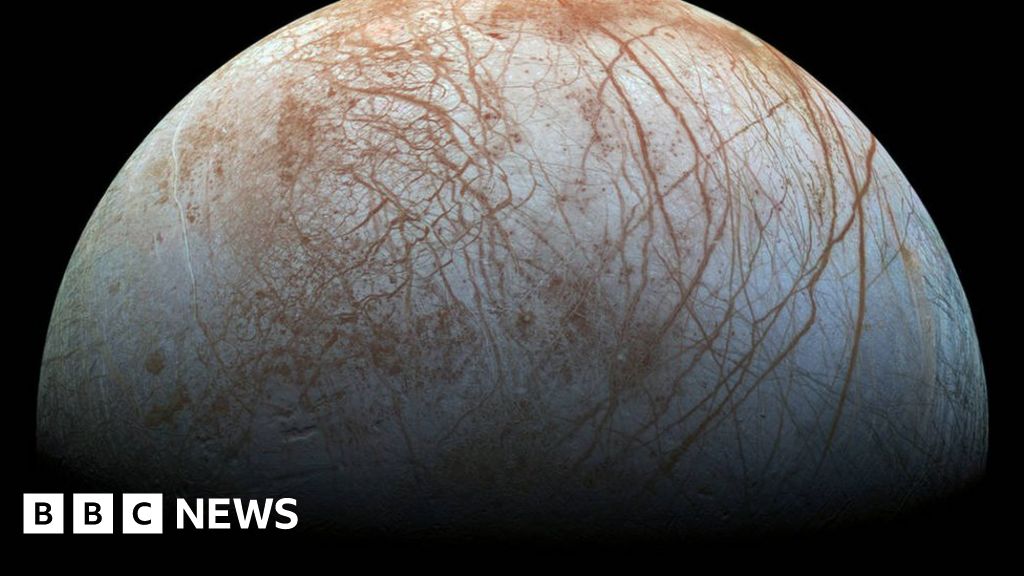

The Earth's magnetic poles (probably) aren't about to flip, scientists say

The Earth’s geomagnetic field, which scientists have been warning about for hundreds of years, isn’t about to suddenly flip over after all, according to a new

Science & Tech

The Earth’s geomagnetic field, which scientists have been warning about for hundreds of years, isn’t about to suddenly flip over after all, according to a new study.

It now looks like the magnetic North Pole will remain in the north and the magnetic South Pole will stay in the south — at least for a few thousand years or so.

“In the geologic time perspective we are currently in a period of very strong geomagnetic field,” geoscientist Andreas Nilsson of Sweden’s Lund University said in an email. “So there is a long way to go before a polarity reversal.”

Nilsson is the lead author of research published this month by the National Academy of Sciences that studied a large weakness in the geomagnetic field known as the South Atlantic Anomaly, or SAA.

The study notes that the Earth’s magnetic field has been getting steadily weaker since the first geomagnetic observatories were established in the 1840s, while the SAA weakness has grown larger over that time.

That’s led some scientists to theorize that the geomagnetic field is decreasing in strength just before it completely reverses direction — something it has done several times in the past, according to layers of rock laid down over millions of years that show previous reversals.

But the new research has found that large geomagnetic anomalies have happened before, and relatively recently in geological time, without causing a field reversal.

These anomalies typically fade away a few hundred years later — and there’s no sign that the SAA will be any different, Nilsson said.

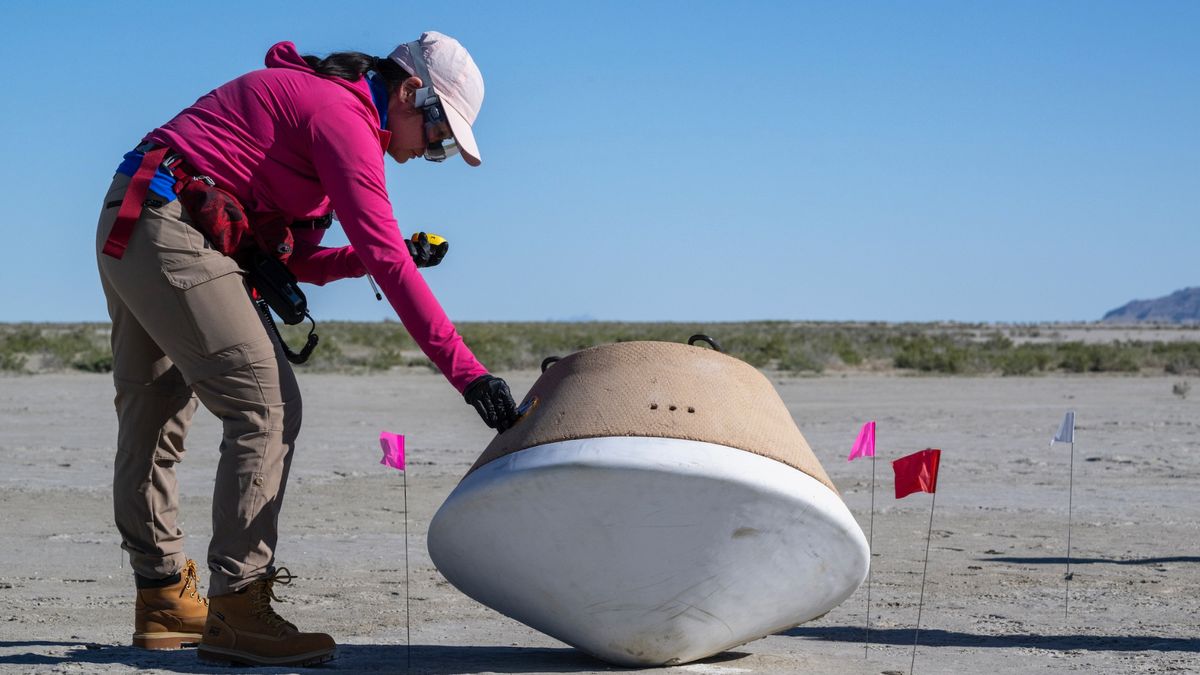

Nilsson and his colleagues studied how the Earth’s magnetic field has changed over the last 9,000 years by looking at the iron in volcanic rocks, ocean sediments and in some cases burned archaeological artifacts.

Those include clay pots fired in ancient kilns thousands of years ago, which sometimes contain small amounts of an iron ore called magnetite. The magnetite lost its alignment when it was heated in the firing process, and the grains became magnetized again by the geomagnetic field when they cooled down, resulting in a record of the field’s strength, Nilsson said.

The study shows that the current state of the Earth’s magnetic field is similar to that of about 600 BC, when it was dominated by two large weaknesses over the Pacific Ocean.

The anomalies over the Pacific, however, faded away over the subsequent 1,000 years, and it’s likely that the SAA will as well, Nilsson said — probably in about 300 years, leaving a stronger and more even geomagnetic field.