www.space.com

NASA's Juno probe will peer beneath the icy crust of Jupiter's moon Europa

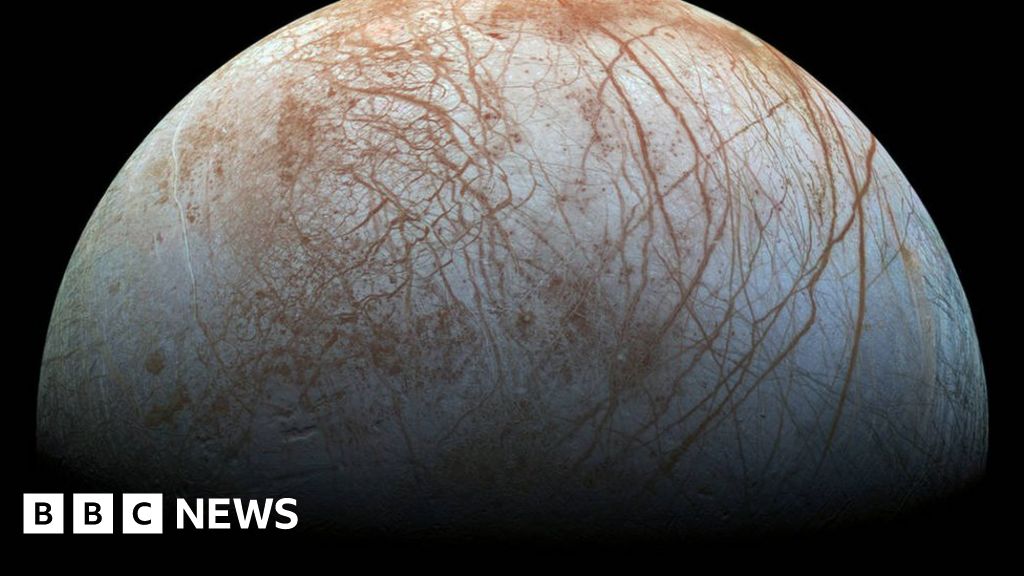

NASA's Juno probe will come closer to Jupiter's icy moon Europa than any spacecraft has in 20 years. Here are Juno's Europa science goals.

Science & Tech

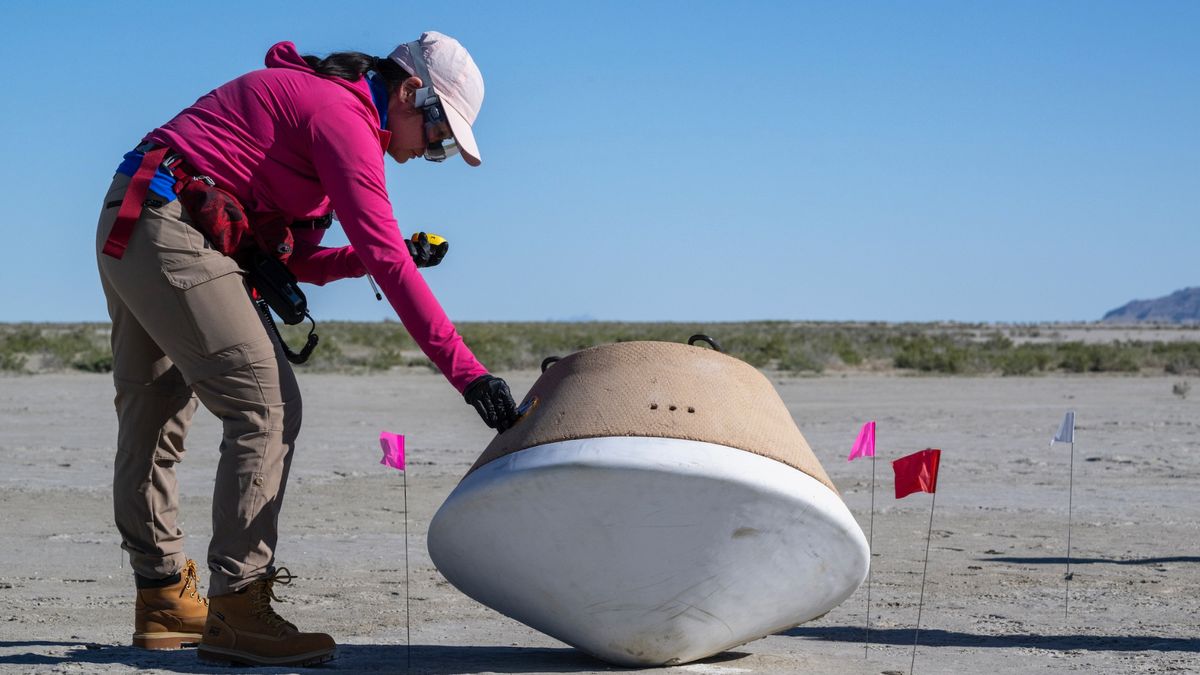

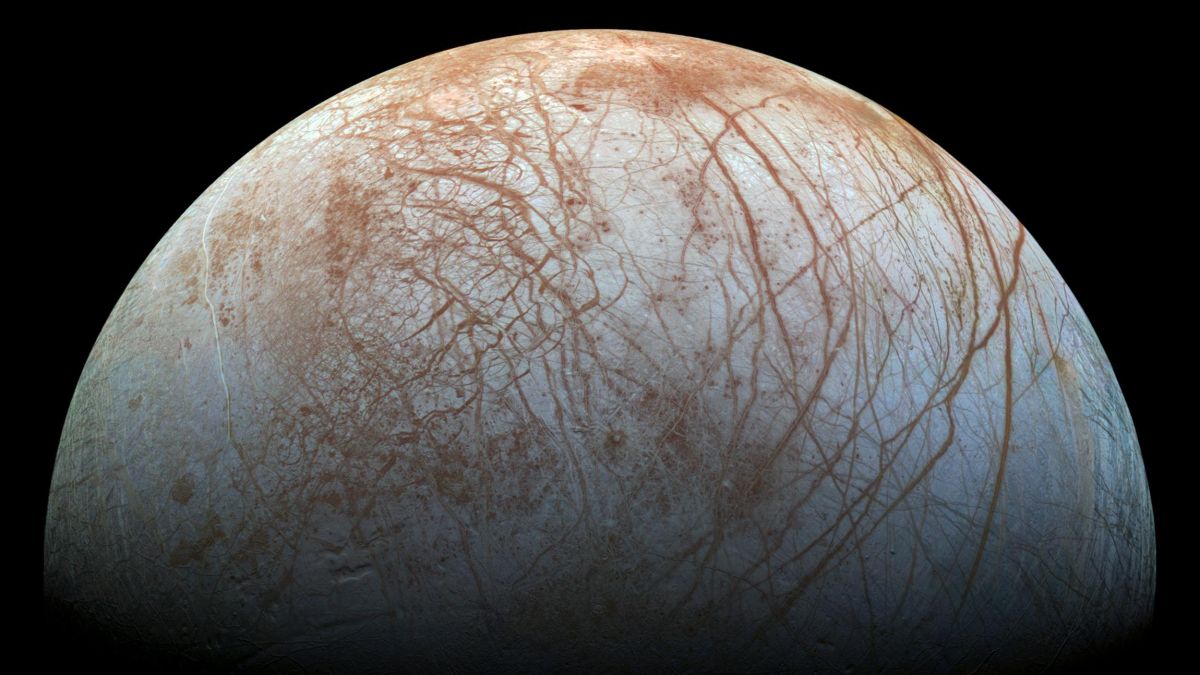

On Sept. 29, NASA's Juno probe will perform the closest flyby of Jupiter's icy moon Europa in over 20 years as the spacecraft embarks on a mission to probe deep into Europa's ice in search of pockets of liquid water.

Europa contains a global ocean beneath a solid crust of ice, making this moon one of the most intriguing places in the solar system to search for extraterrestrial life and one of astrobiologists' top priorities. Although Juno won't be able to tell us whether Europa harbors alien life, it will teach us more about the moon's icy crust, such as how thick it is and whether there are any subsurface pockets of liquid water that could reach the surface.

Juno arrived at Jupiter in July 2016, and its mission has focused on studying Jupiter's atmosphere, from the heights of its ruddy-brown cloud tops to the depths of the lower cloud layers hundreds of miles down, as well as learning about the gas giant's powerful magnetic field and its interior structure all the way down to its core.

In 2021, NASA granted Juno a mission extension and gave it a new aim: to study some of Jupiter's moons. In June 2021, the spacecraft flew within 645 miles (1,038 kilometers) of Ganymede, which, at 3,273 miles (5,268 km) across, is the largest moon in the solar system. Next, it will be Europa's turn, with Juno set to hurtle past the moon at just 220 miles (355 km) above Europa's surface. Juno won't see the entire moon but rather a small fraction of the surface. Yet Juno's cameras have a wide field of view — a bit like that from a smartphone camera — allowing the spacecraft to take in more of the landscape than a normal camera could.

Read here:

https://www.space.com/juno-flyby-jupiter-moon-europa-science