finance.yahoo.com

A Successful U.S. Missile Intercept Ends the Era of Nuclear Stability

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- This month, an intercontinental ballistic missile was fired in the general direction of the Hawaiian islands. During its descent a few minutes later, still outside the earth’s atmosphere, it was struck by another missile that destroyed it.With that detonation, the world’s tenuous nuclear balance suddenly threatened to come out of kilter. The danger of atom bombs being used again was already increasing. Now it’s grown once more.The ICBM flying over the Pacific was an American dummy designed to test a new kind of interceptor technology. As it flew, satellites spotted it and alerted an Air Force base in Colorado, which in turn communicated with a Navy destroyer positioned northeast of Hawaii. This ship, the USS John Finn

Opinion

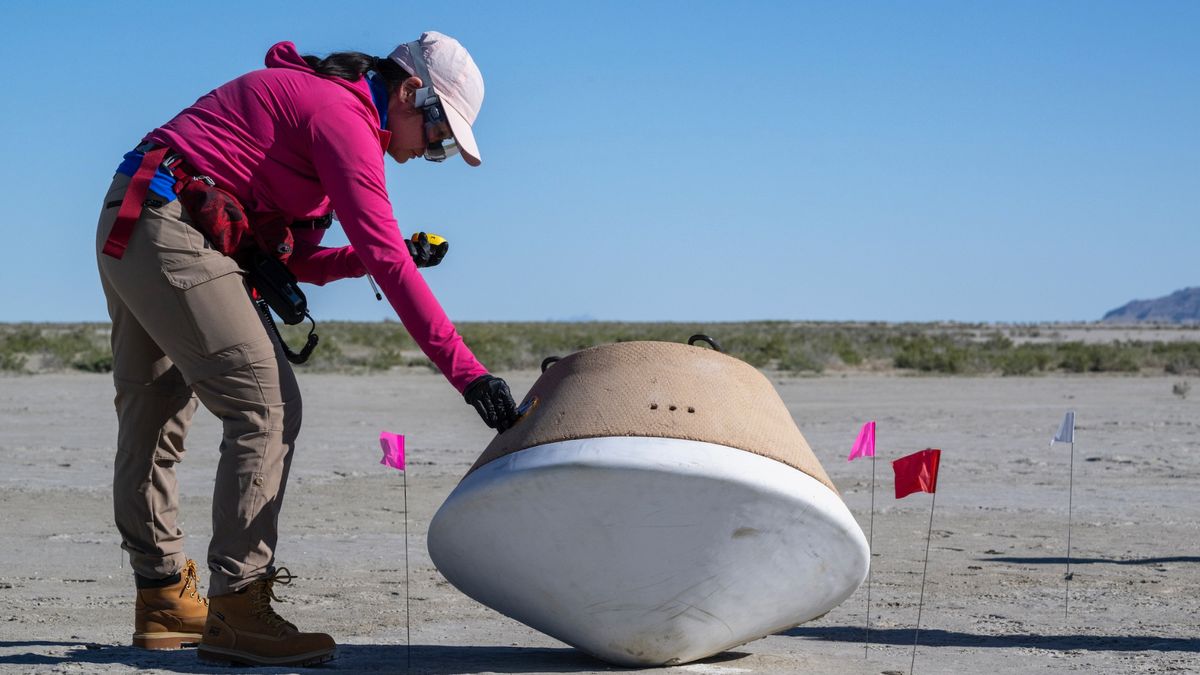

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- This month, an intercontinental ballistic missile was fired in the general direction of the Hawaiian islands. During its descent a few minutes later, still outside the earth’s atmosphere, it was struck by another missile that destroyed it.

With that detonation, the world’s tenuous nuclear balance suddenly threatened to come out of kilter. The danger of atom bombs being used again was already increasing. Now it’s grown once more.

The ICBM flying over the Pacific was an American dummy designed to test a new kind of interceptor technology. As it flew, satellites spotted it and alerted an Air Force base in Colorado, which in turn communicated with a Navy destroyer positioned northeast of Hawaii. This ship, the USS John Finn, fired its own missile which, in the jargon, hit and killed the incoming one.

At first glimpse, this sort of technological wizardry would seem to be a cause for not only awe but also joy, for it promises to protect the U.S. from missile attacks by North Korea, for example. But in the weird logic of nuclear strategy, a breakthrough intended to make us safer could end up making us less safe.

That’s because the new interception technology cuts the link between offense and defense that underlies all calculations about nuclear scenarios. Since the Cold War, stability — and thus peace — has been preserved through the macabre reality of mutual assured destruction, or MAD. No nation will launch a first strike if it expects immediate retaliation in kind. A different way of describing MAD is mutual vulnerability.

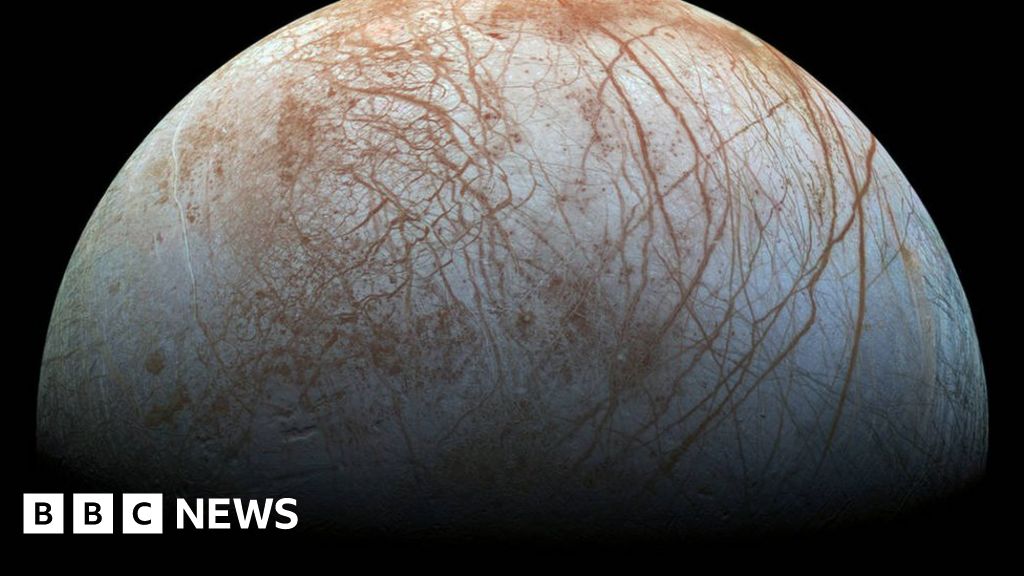

If one player in this game-theory scenario suddenly gets a shield (these American systems are in fact called Aegis), this mutual vulnerability is gone. Adversaries, in this case mainly Russia but increasingly China too, must assume that their own deterrent is no longer effective because they may not be able to successfully strike back.

For this reason defensive escalation has become almost as controversial as the offensive kind. Russia has been railing against land-based American interceptor systems in places like eastern Europe and Alaska. But this month’s test was the first in which a ship did the intercepting. This twist means that before long the U.S. or another nation could protect itself from all sides.

This new uncertainty complicates a situation that was already becoming fiendishly intricate. The U.S. and Russia, which have about 90% of the world’s nukes, have ditched two arms-control treaties in as many decades. The only one remaining, called New START, is due to expire on Feb. 5, a mere 16 days after Joe Biden takes office as president. The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, which has for 50 years tried to keep nations without nukes from acquiring them, is also in deep trouble, and due to be renegotiated next year. Iran’s intentions remain unknown.

At the same time, both the U.S. and Russia are modernizing their arsenals, while China is adding to its own as fast as it can. Among the new weapons are nukes carried by hypersonic missiles, which are so fast that the leaders of the target nation only have minutes to decide what’s incoming and how to respond. They also include so-called tactical nukes, with “smaller” (in a very relative sense) payloads that make them more suitable for conventional wars, thus lowering the threshold for their use.

The risk thus keeps rising that a nuclear war starts by accident, miscalculation or false alarm, especially when factoring in scenarios that involve terrorism, rogue states or conflicts in outer or cyberspace. In a sort of global protest against this insanity, 84 countries without nukes have signed a Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, which will take effect next year. But neither the nine nuclear nations nor their closest allies will ever sign it.

Instead, the existing nuclear powers will interpret news of successful interceptor tests as an impetus for a new arms race. They will make even faster missiles with more decoys and countermeasures, new warheads for more flexible uses in a greater variety of strategic scenarios, and of course their own shields.

This must stop. And the best-placed world leader to take the initiative in halting the madness is the incoming U.S. president. Upon taking office, Biden should immediately propose that the U.S. and Russia roll over New START for another five years to buy time. He should simultaneously invite China and the other nuclear powers to the table.

The first goal should be a declaration by all nine that their nukes have the sole purpose of deterrence and will never be used aggressively. They should also give new assurances of security and help to non-nuclear nations, and create new communications protocols for crises. And yes, they must now agree to limit and monitor not only each other’s offensive weapons but also their defenses.

The era of MAD and mutual vulnerability was terrifying but in a surreal way also stable. The coming era of questionable deterrence and asymmetric vulnerabilities will be less stable and therefore even more frightening. Biden will have much in his inbox come January. He better make sure arms control isn’t at the bottom.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Andreas Kluth is a columnist for Bloomberg Opinion. He was previously editor in chief of Handelsblatt Global and a writer for the Economist. He's the author of "Hannibal and Me."