www.space.com

Confirmed! A 2014 meteor is Earth's 1st known interstellar visitor

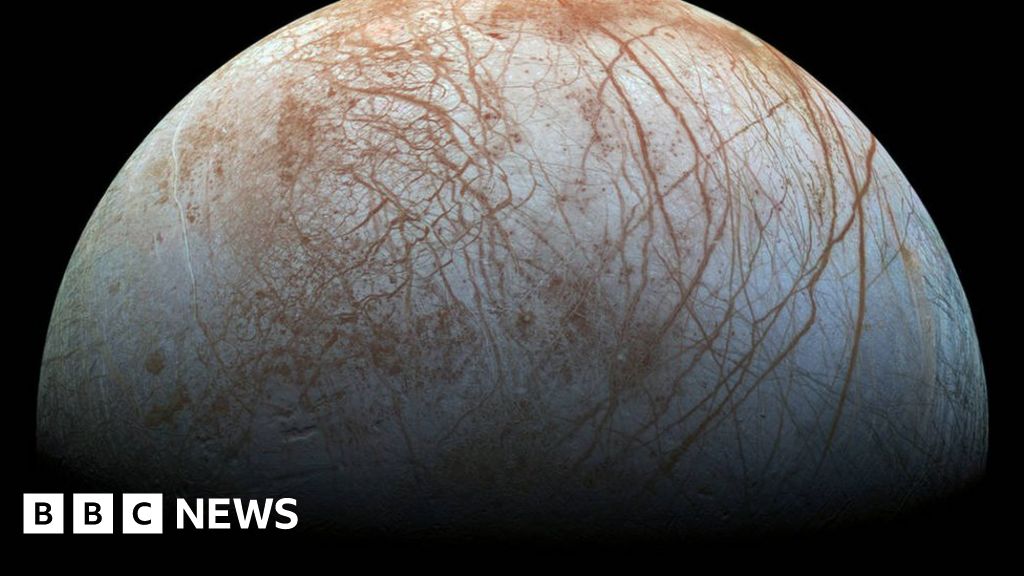

Astronomers have confirmed that a suspicious space rock that hit Earth in 2014 came from another star system, predating the famous interstellar visitor 'Oumuamua by three years.

Science & Tech

Astronomers have confirmed that a suspicious space rock that hit Earth in 2014 came from another star system, predating the famous interstellar visitor 'Oumuamua by three years.

Researchers found the meteor in the catalog of NASA's Center for Near Earth Object Studies (CNEOS) in 2019. At that time, however, some of the data about the rock's trajectory were kept secret by the U.S. Department of Defence (DoD), whose sensors collected them.

But in March this year, the DoD released a statement confirming the measurements, allowing scientists to complete their calculation of the mysterious rock's origin.

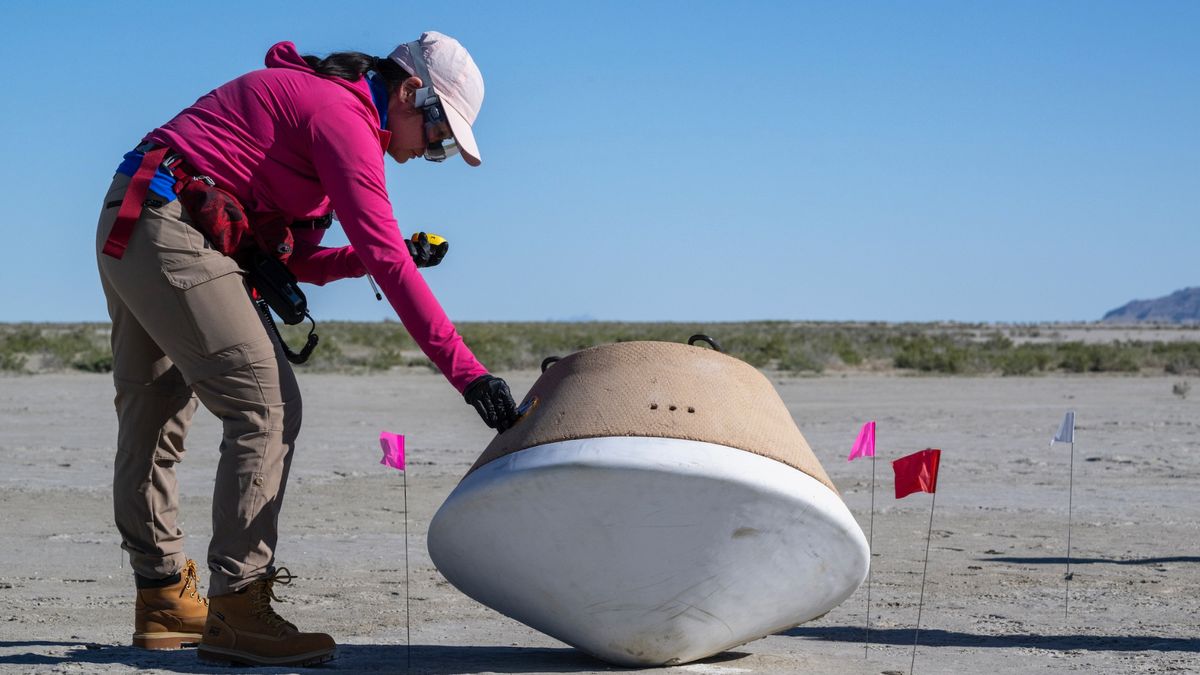

The 3-foot-wide (0.9 meters) mini-asteroid, which entered Earth's atmosphere on Jan. 8, 2014, arrived at a very fast speed of 134,200 mph (216,000 km/h). It also followed an odd trajectory, which suggested it may have come from outside the solar system. By modeling the rock's path into the past and assessing its gravitational interactions with planets in the solar system, the authors of the new paper confirmed the tiny asteroid was, indeed, a newcomer into the sun's corner of the Milky Way galaxy.

The confirmation makes the rock, named CNEOS 2014-01-08, the first known visitor from interstellar space, predating the famous 650-foot-wide (200 m) asteroid 'Oumuamua that zipped past Earth in 2017. Only one year later, astronomers discovered the second interstellar object, the 1,650-foot-wide (0.5 km) comet Borisov. The short interval between those discoveries led astronomers to believe that smaller interstellar rocks, only feet or tens of feet wide, must be much more common in the solar system and even regularly cross paths with our planet.

That's why the authors of the new paper, famed Harvard astronomer Avi Loeb and his colleague Amir Siraj, set out to scour the CNEOS catalog. In addition to CNEOS 2014-01-08, they found another promising meteor, for which the necessary data is still classified, however. That space rock sliced Earth's atmosphere in March 2017.

The researchers believe that interstellar space rocks might hit Earth's atmosphere about once per decade. Analyzing those meteors, the researchers suggest in the paper, could provide new insights into the chemistry of distant star systems.

"By extrapolating the trajectory of each meteor backward in time and analyzing the relative abundances of each meteor’s chemical isotopes, one can match meteors to their parent stars and reveal insights into planetary system formation," the authors said in the paper (opens in new tab). "[Some chemical] elements can be detected in the atmospheres of stars, so their abundances in meteor spectra can serve as important links to parent stars."

Because most meteoroids burn up in the atmosphere before making it to Earth's surface, and because retrieving those that do is extremely time-consuming and challenging on a technical level, the researchers propose creating a worldwide camera network capable of making spectroscopic measurements, analyses of the light-absorption fingerprints of arriving space rocks that could reveal their chemical composition.

CNEOS 2014-01-08 exploded above the ocean near Papua New Guinea, Siraj told Space.com in an email, and the scientists believe that some pieces of the rock may have survived the journey through Earth's atmosphere and fallen into the sea. Siraj and Loeb plan an expedition to attempt to retrieve some of the fragments next year.

The researchers also suggest that such a high frequency of interstellar visitors throughout Earth's history could mean that the seeds of life that had sprouted on our planet in the past 3.5 billion years may have come from another star system.

The study (opens in new tab) was published on Nov. 2 in the Astrophysical Journal.