www.goodnewsnetwork.org

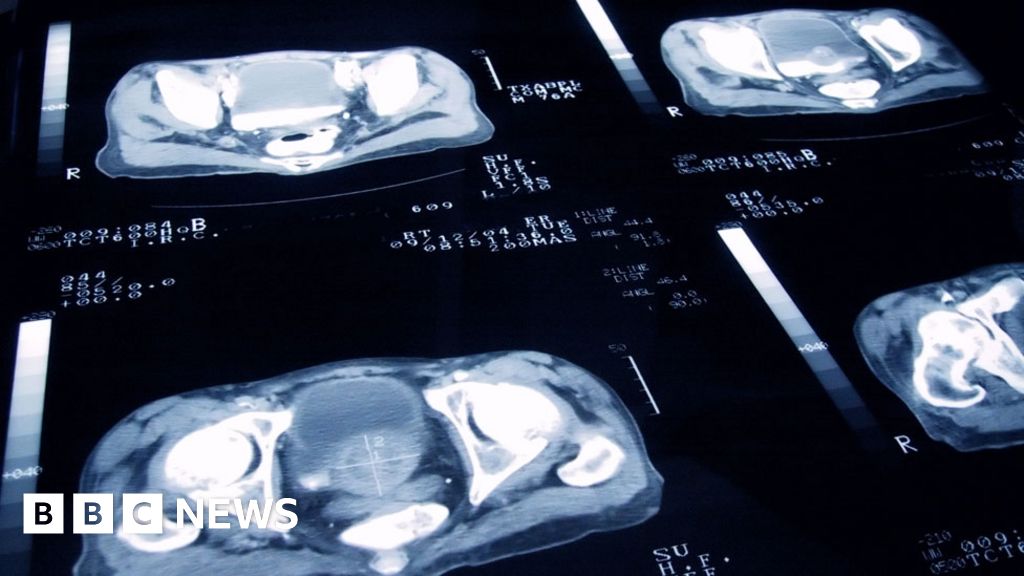

Protein Changes in Blood Could Become New Test for Catching Breast Cancer Up to 2 Years Early

On Wednesday, researchers revealed they found the levels of proteins in people’s blood changed before they were diagnosed with breast cancer.

Science & Tech

Newly discovered protein changes in the blood could pave the way for a new test to catching breast cancer up to two years early.

On Wednesday, researchers revealed they found the levels of six proteins in people’s blood changed before they were diagnosed with breast cancer.

They claimed this could form the basis of blood testing to catch the disease early in those who are genetically predisposed or have a family history of breast cancer, and catching the disease early means a reduced chance of death.

According to the American Cancer Society, the 5-year relative survival rate for breast cancer detected early is just about 99%, but if the cancer is detected late and spreads beyond the breast tissues, that rate falls by about 10%.

These new results came from the “Trial Early Serum Test” Breast, or TESTBREAST, cancer study initiated in 2011.

Currently the study includes 1,174 women who are at high risk of breast cancer because of a family history or carrying gene variants known to raise breast cancer risk.

Women taking part in the study have given blood samples at least once a year for ten years, when they go for a screening. If they develop breast cancer they give samples when they are diagnosed too.

A team from Leiden University made detailed analyses of 30 blood samples from three women who were diagnosed with breast cancer and three who had not.

They discovered distinct differences: a group of six proteins were at higher or lower levels one or two years prior to a breast cancer diagnosis.

Presenting the findings at the 13th European Breast Cancer Conference, Ms. Sophie Hagenaars from Leiden University Medical Center in The Netherlands noted that greater variations in the levels of the marker protein were found in between individuals, rather than in the same individuals overtime.

“This shows that testing should probably be based both on proteins that differ between women with and without breast cancer and on proteins that alter in an individual person over time,” said Hagenaars.

“If further research validates our findings, this testing could be used as an add-on to existing screening techniques. Blood tests are relatively simple and not particularly painful for most people, so people could be offered screening as often as needed.”

Next, the team will try to validate their discovery in a large group of TESTBREAST women with and without breast cancer.

“Women at a high risk of developing breast cancer take part in screening programs at fixed time-points,” said Dr. Laura Biganzoli, co-Chair of the European Breast Cancer Conference, and who was not involved with the study.

“If this research ultimately results in a blood test for people with a high risk of breast cancer, that could guide personalized screening and help to diagnose breast cancer at the earliest possible stage.”