www.nbcnews.com

A view from Crimea, the Russian-annexed territory Ukraine wants back

NBC News took a rare trip inside Crimea, the peninsula annexed by Russian President Vladimir Putin in 2014 and now a target for Ukraine ahead of new offensives.

International

SEVASTOPOL, Crimea — Soldiers kiss women and children goodbye at train stations. Fighter jets circle overhead. Military vehicles bearing nationalist Z's on their grills power down the Tavrida Highway, a 155-mile road linking this peninsula’s main cities.

Crimea is a territory teeming with Russian forces.

Nowhere is that truer than in Sevastopol, a city that has long embodied naval might in the Russian imagination.

Fishermen watch as Russia’s Black Sea Fleet docks and sails. “Special Military Operation for the future of Russia,” declares a billboard en route to the port. Sevastopol’s “Victory” cinema now also sports a massive Z. Roads like Lenin Street are lined with red, white and blue Russian Federation flags.

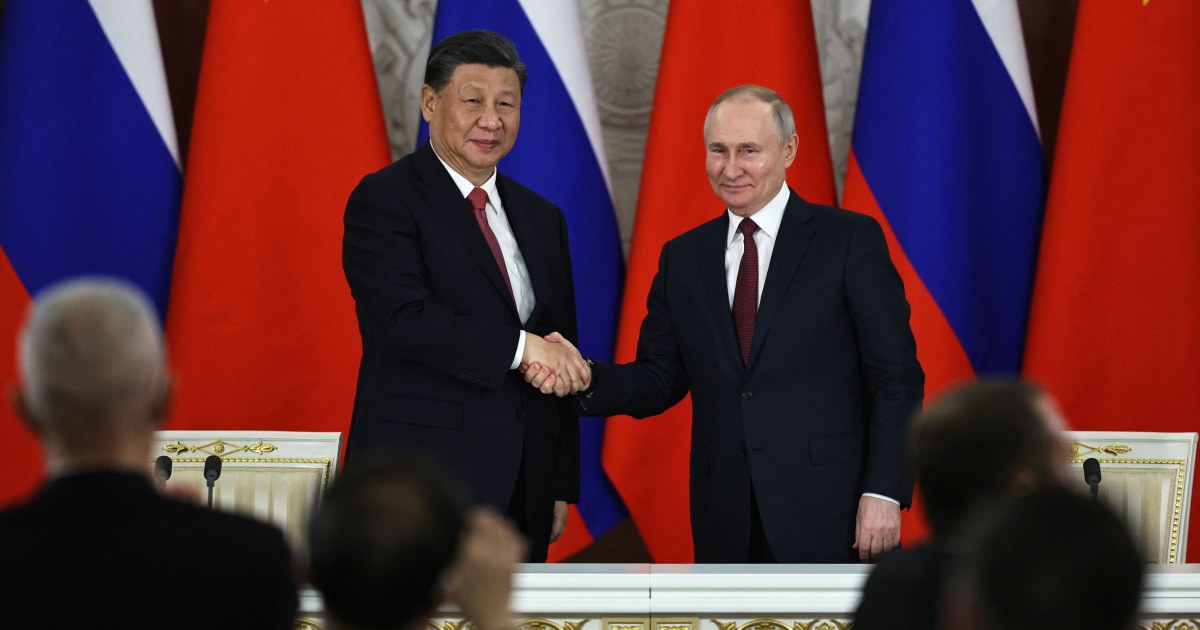

This is not Russia, according to Kyiv, its Western allies and the United Nations. It was annexed by the Kremlin in 2014, with the U.N. calling on Russia to return to its ‘internationally recognized borders.’ And following Moscow’s broader invasion launched a year ago, President Volodmyr Zelenskyy has vowed Ukraine will take Crimea back.

But Praskovya Baranova, 73, speaks Russian, feels Russian and lives here.

“This is our land,” she told NBC News on Monday. “We will all put on uniforms and will go to the border to defend ourselves.”Her comments echoed those of most people NBC News spoke to in Crimea this week. While the government of President Vladimir Putin has cracked down on free speech everywhere, including in Crimea, the peninsula’s majority Russian-speaking population was considered more pro-Moscow than other parts of Ukraine when it was annexed.

Russia says life has improved.

Modern-looking gas stations along the highway sell Coca Cola imported from Belarus, a beverage hard to find in Moscow these days.

But Zelenskyy has said Crimea is one of the reasons he wants more powerful NATO weapons. “Crimea is our land, our territory,” he said in January. “Give us your weapons—we will return what is ours’. And if Ukraine does try to take the peninsula back by force as its leaders have promised, many of the 2.4 million people living here will be caught in the middle.

“He wouldn’t take it,” Ruslan Nalgiev, 36, said. “Even if there is a war here, we would still defend Sevastopol. Because if we don’t defend our motherland we would become slaves. No one wants to become a slave.”

Sevastopol — home to Russia’s Black Sea Fleet in Soviet times and the era of the Russian empire — might be the king on Putin’s chess board: The Russian leader may be determined to protect it at any cost, but Kyiv may now fear any peace deal that left Russia’s navy in the port would threaten its coastline for years to come.

After explosions rocked strategic sites in Crimea and Kyiv’s forces seized back the nearby southern hub Kherson late last year, the door appeared to be open to a campaign to retake the prized peninsula. But Russian forces have regrouped and dug in.

NBC News traveled to Crimea by train from Moscow, across the Kerch Bridge that was blown up in a strategic and symbolic blow to Putin last fall. It is now fully restored but would likely be targeted again if the fight came to this peninsula.

Doubts persist, however, about whether the United States and other allies are willing to give Ukraine the firepower it may need for such an ambitious operation — especially given the Kremlin’s stance that Crimea represents a red line.

“The question of Crimea, and the question of what happens down the road, is something that we will come to,” White House national security adviser Jake Sullivan said on NBC News’ “Meet the Press” Sunday. Under Secretary of State Victoria Nuland recently said that ‘at the very least Crimea needs to be demilitarized,’ though she didn’t say how that could be done.

Sevastopol is steeped in Russian military culture. It even has a Russian Army Store with toy tanks, Kalashnikovs and artillery for kids. For adults it stocks clothes with “Victory is ours” emblazoned on them.

With war just a few hundred miles away, there are now makeshift signs for the nearest basement in Sevastopol.

Resident Diana Galastyan, 26, denies that the Russian authorities may be trying to scare people. “No one imposes fear on us. No one is saying to us that it will be scary. Nothing like that. They don’t plant fear in us.”

Still, fear lives here if you look for it.

A U.N. committee recently accused Russia of extra-judicial killings, abductions, politically motivated prosecutions, discrimination and violence in Crimea. The target of many of these human rights abuses, it said, were Crimean Tatars, a Muslim ethnic minority that has been oppressed over the years and which has often led the opposition to Russia’s rule.

For a community like this one, speaking out can be frightening.

In the historically Tatar village of Bakhchisarai, Olgar, who declined to give her last name, broke down in tears when she talked about the war.

“All mothers are crying. Both Russian and Ukrainian mothers are crying,” she said. “Why did it even start? Can’t we all live in peace? Can’t we just share this piece of bread in two halves?”

Now the conflict is threatening to once again engulf Crimea.

Zelenskyy has said the war that started here will end here, a prospect that — for residents of the peninsula and the rest of this war-torn region — may mean an end to the bloodshed is a long way off.

“I have lived a long life already and I always thought that our generation would live without the war,” Olgar says. “And you see, I was mistaken.”