www.nbcnews.com

The ballooning U.S.-China rivalry has countries reluctant to pick sides

The escalating dispute between the United States and China over a downed Chinese surveillance balloon has left many countries stuck in the middle.

International

HONG KONG — A large balloon may be a novel cause of strife between two major powers, but the escalating dispute has put many countries in a familiar position: stuck in the middle of the United States and China, and not happy about it.

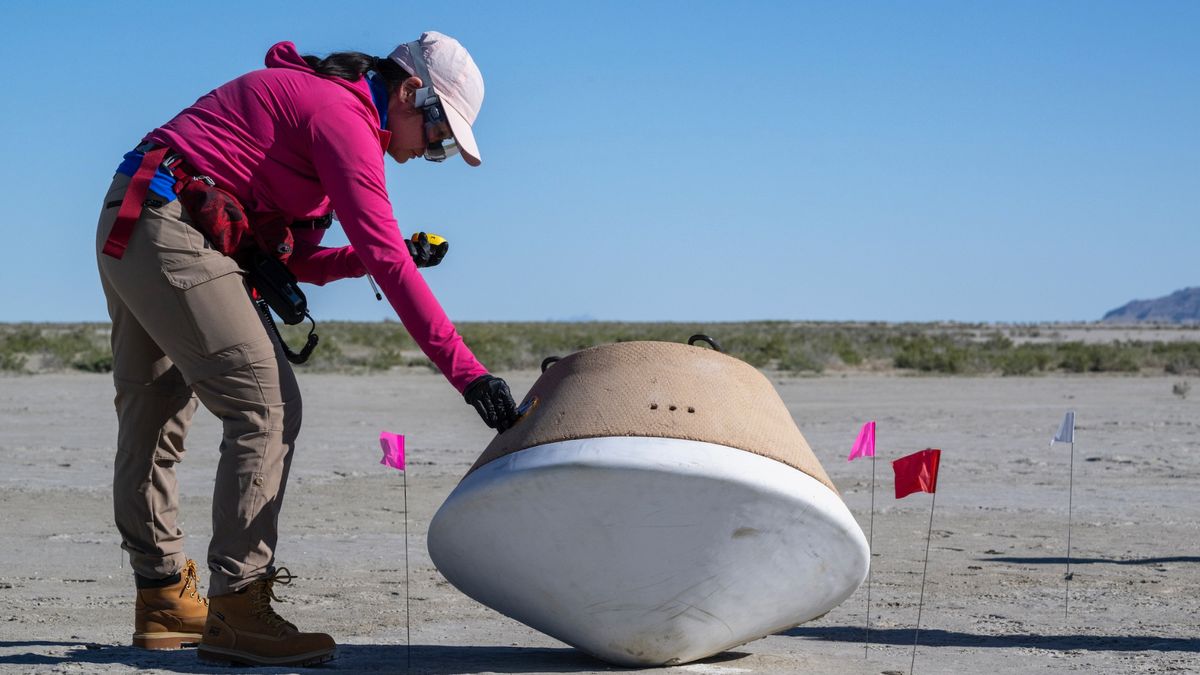

Like so many clashes between Washington and Beijing, the downing of a Chinese surveillance balloon by the U.S. military has rippled across the world, drawing in U.S. allies: jets scrambled in Europe, new displays of public unity from South Korea and Japan and debates over security in Britain.

Diplomatic competition between China and the U.S. has been intensifying from Africa to the Pacific with deals on trade and military bases, while both seek to persuade existing allies to reevaluate their ties with the other side. For many countries, however, the balloon saga is just the latest tricky issue to navigate as they try to balance relations with the world’s two largest economies.

That may explain why Southeast Asia, at the forefront of the tensions, has been relatively silent on the balloon incident, said Collin Koh, a research fellow at the Institute of Defense and Strategic Studies at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore.

“Even if you consider that some countries might have encountered similar sightings, they are not inclined to talk about it,” he told NBC News, “because they do not want to be drawn into what they see as a largely Sino-U.S. rivalry.”

From Taiwan to Romania

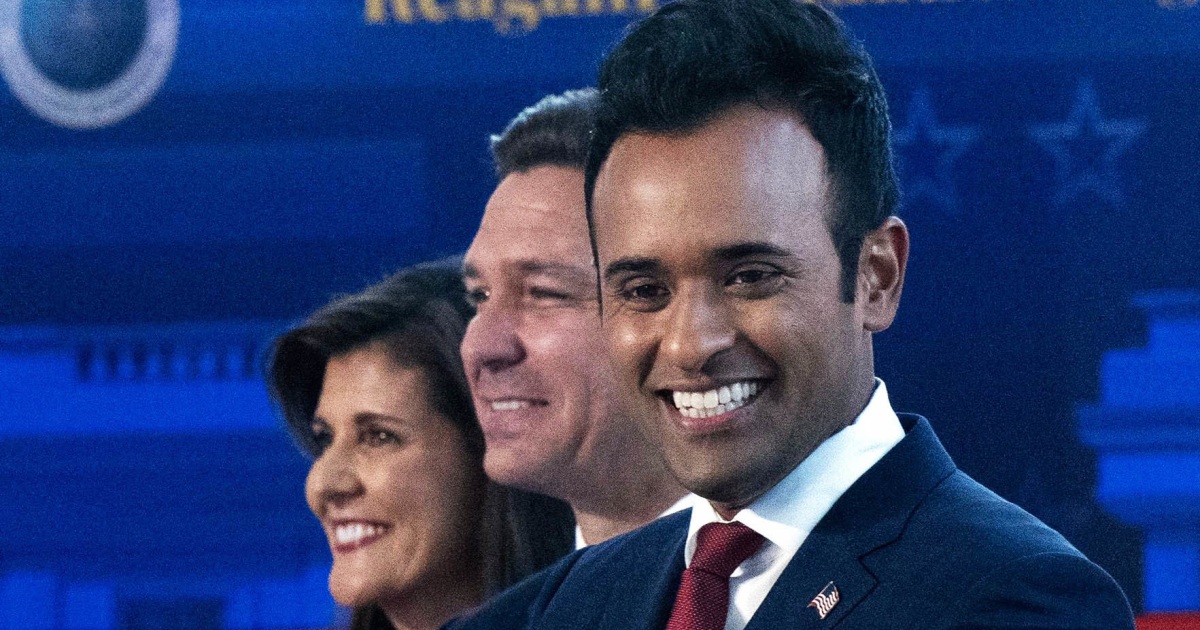

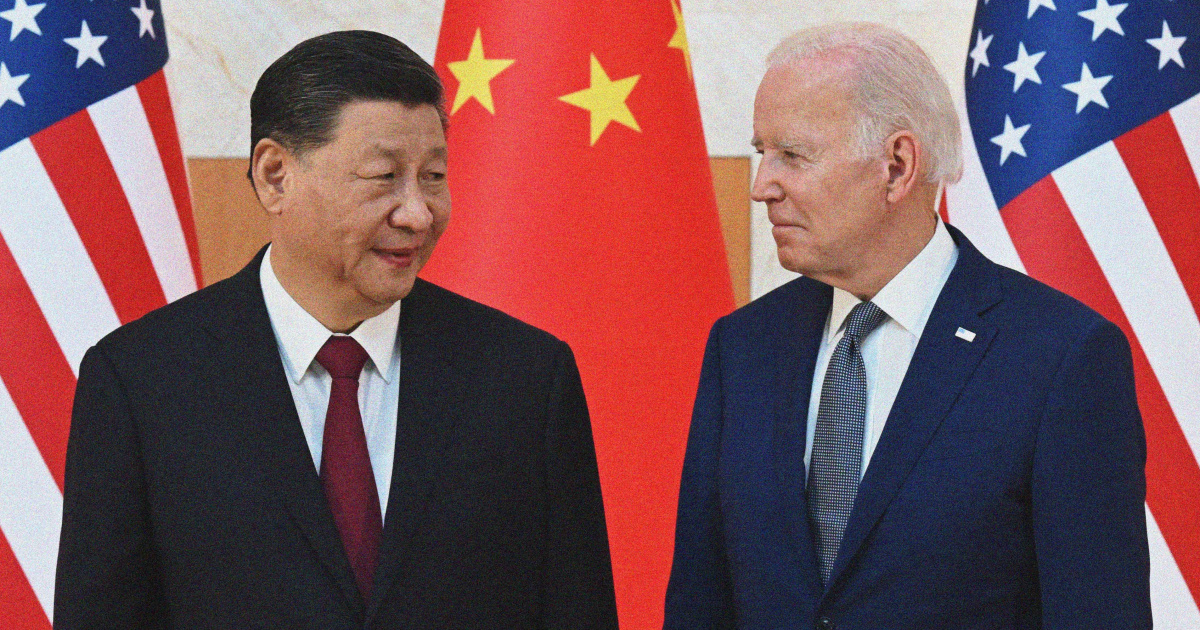

In an exclusive interview with NBC News on Thursday, President Joe Biden said “the last thing” Chinese President Xi Jinping wants is for U.S.-China relations to be further damaged by the suspected spy balloon downed over American territory, and that he planned to speak with the Chinese leader about the incident.

U.S. officials say Chinese surveillance balloons have crossed over dozens of countries across five continents. They have briefed countries on the issue in recent days, prompting some to re-evaluate past sightings of unidentified aerial objects in their own territory.

Japan said that three objects detected in its airspace in recent years were now “strongly presumed to be unmanned reconnaissance balloons flown by China.” Beijing responded that Tokyo “needs to be objective and impartial on this instead of following the U.S.’s suit in dramatizing it.”

NATO, the Western military alliance, is also on high alert. Two Romanian military planes under NATO command were deployed Tuesday in response to the detection of a high-altitude object, but did not confirm its presence. In Britain, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak said airspace security would be reviewed.

But Europe — especially leading power Germany — has generally remained reluctant to distance itself from China as fully as the U.S. might hope, despite deteriorating relations over human rights issues and Beijing’s tacit support for Russia's war in Ukraine.

And fears over high-altitude balloons may not land as hard in Asia, where China is building artificial islands in the South China Sea, clashing with foreign vessels and sending warplanes toward Taiwan almost daily.

Taiwan, a self-ruling island that Beijing claims as its territory, has largely played down any balloon threat, though the army said Thursday that it had found the remains of what appeared to be a crashed weather balloon on a remote island near the Chinese coast. The response from Southeast Asia has been similarly low-key.

“They’ve probably got limited capability to prevent China from doing this kind of thing and so they would rather not make a big deal out of it,” said Susannah Patton, director of the Southeast Asia program at the Lowy Institute, a think tank in Australia.

Playing ‘both sides’ of the balloon

Many countries in Asia and beyond also see U.S.-China tensions as standing in the way of progress on issues of global importance like climate change and public health, and have urged greater communication.

Vietnam said it hoped that Beijing and Washington would continue to resolve disagreements through dialogue, while Singaporean Foreign Minister Vivian Balakrishnan lamented the U.S. decision to postpone Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s trip to China over the balloon incident.

“The more they engage, the more they meet, the more open lines of communications, the better,” he told reporters.

China, meanwhile, is moving ahead with other diplomatic efforts.

Xi met in Beijing this week with Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi, and China’s top diplomat, Wang Yi, is on a weeklong trip to Europe that includes a stop in Russia in what could be a precursor to a Moscow trip by Xi. China, Iran and Russia often present themselves as counterbalancing Washington’s global dominance.

Many countries view the world as increasingly multipolar and are seeking to diversify their diplomatic ties, said Madiha Afzal, a foreign policy fellow at the Brookings Institution in Washington.

“They don’t see this world now as being led by China or led by the U.S. only,” she said. “It benefits them to have relationships on both sides.”

Talk of an emerging cold war between the U.S. and China has also raised suggestions of a new “nonaligned movement” of countries that hope to stay out of it.

During the decadeslong conflict between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, 120 mostly developing countries — many of them newly independent — established a loose coalition by that name that is now one of the largest international forums in the world.

Countries torn between the U.S. and China are reluctant to choose sides mainly for economic reasons, said Wu Xinbo, director of the Center for American Studies at Fudan University in Shanghai.

“They basically cannot live without the U.S., but they are also inseparable from China, because China is the largest trading partner of more than 120 countries and regions,” he said.

He cited sweeping U.S. export controls on strategically important semiconductor chips that are pushing China to develop its own technology, which Wu said could “divide the world into different parts economically.”

In that context, Afzal said, harsh U.S. criticism of other countries’ relationships with China could backfire. The U.S.-China competition for allegiance might also “grant undue leverage” to the more powerful countries that resist taking sides, she said.

Balakrishnan, the Singaporean foreign minister, argued for a new “nonaligned movement” at a conference late last year, emphasizing the importance of international cooperation for science, technology and supply chains.

“I don’t believe any self-respecting Asian country wants to be trapped, or to be a vassal, or worse, to be a theater for proxy battles,” he said. “Whether we will actually achieve this, only time will tell.”